One of the most memorable scenes in Russian literature relates the thoughts of a man lying on the ground staring at the sky in the middle of a major European battle. Prince Andrei Bolkonsky is wounded. He is placed in a situation where, instead of running, fighting, and thinking every moment might be his last, he is suddenly met with silence, grandeur, tranquillity. Instead of everything being horror, deception, and emptiness, he sees only peace and infinity, and for this he is grateful. His desire for life is affirmed.

Nor does he forget his experience when caught in a place of extreme vulnerability on a battlefield. Later, when Prince Andrei as it happens encounters the architect of Austerlitz in person, he finds Napoleon wanting, “so petty did his hero with his paltry vanity and delight in victory appear, compared to that lofty, righteous and kindly sky which he had seen and comprehended.”

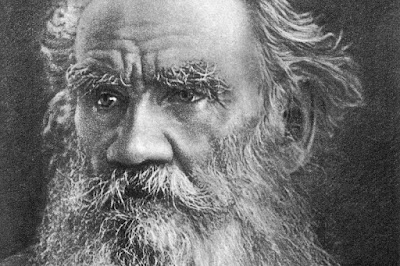

Count Leo Tolstoy’s wondrous contrast invites us to see beyond the insidious demand for attention generated by war. It is also a leitmotif for Tolstoy’s whole life. His view of war changes through time, becoming more critical and pacifist, but it is already forming in the novel where he contrasts the worlds of war and peace, their contradictory values, and distressingly different prospects. By the time he adopts the life of a Christian social activist and agrarian, his language on this subject has grown polemical and ferocious.

“That nations should not be oppressed, and that there should be none of these useless wars, and that men may be indignant with those who seem to cause these evils, and may not kill them – it seems that only a very small thing is necessary.” This is Aylmer Maude’s translation of words in Tolstoy’s pamphlet ‘Thou Shalt Not Kill’ (1900), an article prohibited in Russia, while its German version was seized and all copies destroyed as “insulting to the German Kaiser.” What is necessary? “It is necessary that men should understand things as they are, should call them by their right names, and should know that an army is an instrument for killing, and that the enrolment and management of an army – the very things which kings, emperors and presidents occupy themselves with so self-confidently – is a preparation for murder.” Tolstoy argues that people go along with their leaders because they are hypnotized by what is going on, the pomp, the power, the false motives. Men are stupefied into becoming “instruments for murder”. It’s not one particular person who causes oppression and wars. The misery of nations is caused “by the particular order of society under which the people are so tied up together that they find themselves all in the power of a few men, or more often in the power of one single man: a man so perverted by his unnatural position as arbiter of the fate and lives of millions, that he is always in an unhealthy state, and always suffers more or less from a mania of self-aggrandizement, which only his exceptional position conceals from general notice.” Tolstoy concludes by saying “we may help to prevent people killing either kings or one another, not by killing – murder only increases hypnotism – but by arousing people from their hypnotic state.”

Between

these two publications, Tolstoy wrote a tale that James Joyce said in a letter

to his daughter is “the greatest story that the literature of the world knows.”

In ‘How much land does a man need?’ (1886) a peasant woman says to her sister, “All

may be well one day, the next the Devil comes along and tempts your husband

with cards, women and drink. And then you’re ruined. It does happen, doesn’t it?”

The husband hears this and complains that his only grievance is that “I don’t

have enough land. Give me enough of that and I’d fear no one – not even the

Devil himself!” But the Devil has been listening the whole time and decides to

play “a little game” with the man. The husband

finds more and better and larger deals for acquiring land, sowing crops, building

impressive homesteads, and all the time the land deals get more outrageous, and

further away from his home in distant provinces. The more land he gets the more

land he wants, to the point where he exclaims “If I stopped now, after coming

all this way - well, they’d call me an idiot!” Eventually he is tempted by a

land claim so exorbitant that it brings about his own demise. Without spelling

out the moral, Tolstoy’s concluding sentence records the husband’s workman digging

his grave, “six feet from head to heel, which was exactly the right length –

and buried him.”

Comments

Post a Comment