Some thoughts while reading ‘The Age of Disenchantments’, Aaron Shulman’s biography of the Panero family

The debt that Aaron Shulman owes to the writings, published and unpublished, of Felicidad Blanc increases with each chapter. His adoption of the thoughts and feelings of each member of the Panero family is especially prevalent in her case, prompting the reader to ask: where did he get this emotional inside knowledge? The answer is simple: from her own writings, published and unpublished, listed in the book’s bibliographies. Shulman nowhere acknowledges that that’s what he is doing, an act of appropriation of her words that leaves one with an uneasy feeling. On the one hand, he is forthcoming about Felicidad’s own literary ambitions, while on the other he plays his own game of storyteller by using her primary source material for his own ends. This results in a literary history that at times tips into novelistic imaginings of each main character, and notably Felicidad herself. Although he ponders from time-to-time why these people behave in such truly crazy ways, it is not hard to see that the literary and social ambitions of Felicidad herself are a prime inspiration and personal challenge to all the males in her family.

This manner of fact/fiction writing leaves little for the reader’s own imagination, as we adjust to Shulman’s recreation of how he interprets Panero family behaviour. But it can be explained in terms of the infamous documentary ‘El Desencanto’ (1976). This film is mentioned in the introduction but only gets full treatment late in the book, at its place in the century-long chronology of the Panero family. The Paneros’ flair, which is also a hunger, for self-promotion is outrageously on show. Mother and sons display little self-restraint as they rave on about their messy family relationships, scarcely able to conceal the unpleasant rivalries and desires that cross generations. We see that this is Shulman’s original encounter with the Paneros, his research being an extended response to the implications of the film. He sets out the ambitious dynamics that would end up on show in such a self-important, self-dramatising film. Shulman explains the spectacle well. Yet the author himself has entered the family saga with his own version of what he is seeing and reading, a kind of Spanish novel all of its own. Shulman’s temptation to be melodramatic, at times, is almost as great as his subjects’, where melodrama is one of the elements they breathe in and out each day.

This focus on the psychodramas of successive generations could have been improved and lifted by the one thing the Paneros all rely on for their story: their writing. For a book about poets, there is surprisingly little of their poetry. Likewise, Felicidad’s prose and short stories remain largely unseen, except as used and interpreted by Shulman. Quotation without editorialising would have given the reader opportunity to make their own judgements. Added to this, we never hear the men’s poetry in Spanish, or only rare snatches. A first-time English encounter with the Paneros could do with plenty of poetry, which is after all the heart of the matter for each of the poets. On the evidence inside but especially outside the book, Leopoldo Panero, Leopoldo María Panero, and Juan Luis Panero are three people extravagantly expert at telling us their innermost thoughts.

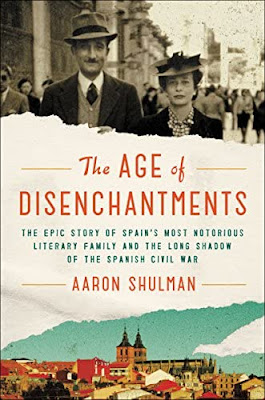

Still, we are being given a history. We are given an excellent picture of how the Spanish Civil War divided families, and continued those divisions long after 1939; how the War forced people to take sides against their own better judgement; how compromise turned into uncomfortable allegiances; and survival was not assured. We can understand the rebellion of the sons against the father, but must also understand the father’s own changing position from Republican to Francoist, and the ultimate cost of that choice. Shulman’s weaving of national history with Panero history turns into the real triumph of his book. Readers outside Spain are given a first-time panorama of what many Spaniards have lived with for quite a while, what the sub-title calls “the epic story of Spain’s most notorious literary family.” Speaking the unspoken continues as a thematic drive throughout the narrative.

Doubtless there has been work done on the relationship between Pablo Neruda’s ‘Canto General’ (1950) and Leopoldo’s fierce rejoinder to that collection, ‘Canto Personal’ (1953). While I understand ‘desencanto’ to mean ‘disenchantment’, what do we make of ‘desen-canto’ or ‘Desen Canto’? I expect it conjures several meanings. The terrible breakdown between Panero Snr. and Neruda was brought about by political betrayal, civil war, and ostracization. It is striking how many people in this story stop talking to one another, and how Spanish society under Franco made that easy to do and justify. The different sides keep their distance. They spend more time protecting their territory than building bridges. The Chilean Neruda understood exile better than any of the Paneros, such was the cost of having to take sides and maintaining a front for the regimes. Their falling-out is one dramatic example of friends turning foes though external circumstances, each playing public roles that they would once upon a time have regarded as impossible, back in the day.

Comments

Post a Comment