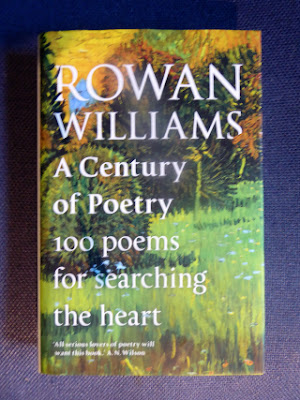

An anthology of 100 poems written in the past 100 years, with readerly responses on each from Rowan Williams, is a kind of autobiography of the archbishop’s roving mind. Titled ‘A Century of Poetry’, the book’s subtitle gets to the point with the claim that we are “searching the heart.” This is not a best-of or my-favourites collection, but one where poems “open the door to some fresh, searching, and challenging insights about the life of faith.”

The English poet Michael

Symmons Roberts opens ‘A New Song’:

Sing a new song to the Lord,

sing through the skin of your

teeth,

sing in the code of your blood,

sing with a throat full of earth

To which Rowan asks, why do we

praise? Then answers, “praise is as inescapable as lament in the human world.

The singing evoked here is not a full-throated self-indulgent performance; it

is what manages to escape from choked and knotted insides because it can’t be

contained; and it names or at least points towards what can’t be named.” His

readings, over and again, are interested in the contradictions in our

inheritance, how questions keep rising up that must be asked and considered.

Roberts concludes

sing what you never could say,

sing at the fulcrum of joy,

sing without need of reply.

Rowan Williams is a maker of

poetry and this is a guidebook to the sorts of poems he would perhaps like to

make himself; we detect many of his own poetic interests and stylistic

tendencies in this admiring selection. For example, the Pakistani-Scots poet

Imtiaz Dharker’s poem ‘Prayer’ is not a world away from Rowan’s own manner:

The place is full of

worshippers.

you can tell by the sandals

piled outside, the owners’

prints

worn into leather, rubber, plastic,

a picture clearer than their

faces

put together, with some originality,

brows and eyes, the slant

of cheek to chin.

“What prayer are they whispering?” she asks. Rowan writes, “the worn sandal as ‘the perfect pattern of a need’ is the central image of the poem, Each of the sandals left at the door of the mosque has a unique set of indentations, a unique history of being pushed into this distinct shape by the unavoidable daily pressure of keeping moving.” Each sentence of his reading extends the meanings and ambiguities of Dharkar’s poem into a satisfying reflection on her own more concise argument. One example: “Dharkar … gives us an austerely compelling picture of what prayer actually is: it is something as inescapable as walking, something that has to do not with anxious petitioning or ecstatic thanksgiving but with the sheer hope of moving, or perhaps growing, into a future.”

Understandably, Welsh poets are well-represented.

Gwyneth Lewis, in ‘How to Read Angels’, writes of the encounter:

Yes, information, but that’s

never all,

there’s some service, a message.

A lie dispelled,

something forgiven, an alternative

world

glimpsed, for a moment, what you

wanted to hear

but never thought possible. You

feel a fool

but do something anyway …

Rowan identifies some rules of

thumb about angel voices: “Truthfulness, forgiveness, hope – these are reliable

signs that whatever has been sensed or guessed at is more than just the

contents of our own mind … What is convincing is the surprise that something we

wanted might after all be thinkable.” Discovering what might be thinkable is a

hallmark of this book.

The Indian novelist Vikram Seth

took up residence in the Old Rectory at Bemerton, outside Salisbury, the home

of poet George Herbert for a brief time in the seventeeth century. Rowan says Seth’s

background is Hindu, but in this context it’s true to say his background is

also decidedly Christian. His list poem called ‘This’ includes the following

items:

A beast of light; a blaze to

quench or stoke;

Bread burst and burnt; sweet wind-fall;

storm-cloud-milk;

Hope raised and razed; skin-ploy; sleep-foil;

steel-silk …

Seth once wrote a novel

composed entirely in Pushkin sonnets, so he is right at home here writing a

sonnet about love (the answer to the riddle) emulating Herbert’s about prayer. “Like

all good metaphorical speech, the succession of images sets out the

contradictions that push us into poetry,” writes Rowan, saying that Seth’s poems

“prompt some lingering on the frontier of ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’ experience,

some questioning about how porous those boundaries are.” This porousness is

something Rowan Williams explores again and again in this book, just as he does

in so much of his writing, and poetry. Poetry’s appeal to experience opens up

our shared knowledge, something being foregrounded here all the time.

Australian Les Murray’s oft-quoted

‘Poetry and Religion’ goes

Religions are poems. They concert

our daylight and dreaming mind,

our

emotions, instinct, breath and

native gesture

into

the only whole thinking: poetry.

Rowan

applauds Murray’s avoidance of cliché, chiming in with his shared view that “poetry

aims to do in a small space what religion does in a large, communal and

historically extended space: to hold a mirror to a formidable range of

shifting, threatening, exhilarating ‘givens’ that require us to adjust to their

presence and make sense of them.” This is another way of meeting and enjoying

the many ideas and experiences offered here. I have briefly quoted just five poems

that are part of an ongoing conversation Rowan Williams generates in this book.

The invitation is there to pick up a line, a verse and see where it takes you.

Comments

Post a Comment