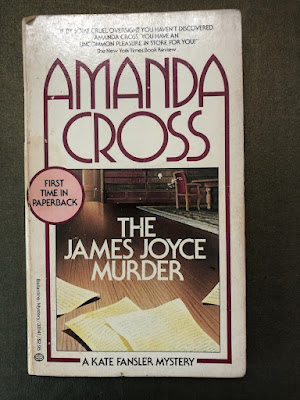

Bloomsday Novels 1967 (American): ‘The James Joyce murder’, by Carolyn Gold Heilbrun, writing under the penname Amanda Cross

One of the novels written about by Philip Harvey for his paper (‘A Hundred Bloomsdays Flower : How Writers Have Remade Joyce’s Feast Day’) on Bloomsday in Melbourne, 16th of June 2023 and read at the annual seminar upstairs at the Imperial Hotel, corner Bourke and Spring Streets in Melbourne, on Sunday the 18th of June.

The Prologue to Amanda Cross’s ‘The James Joyce murder’ opens thus:

James Joyce’s Ulysses, as almost everybody knows by now, is a long book recounting life in Dublin on a single day: June 16, 1904. It was on June 16, 1966, exactly sixty-two years later, that Kate Fansler set out for a meeting of the James Joyce Society, which annually held a “Bloomsday” celebration. (Cross 9)

Fansler is a literature professor at a New York university, and also a detective, all fourteen books in the Kate Fansler series (1964-2002) having connections with academe and publishing. This is the third in the series.

Adopting

what she hoped was a properly Joycean attitude, Kate reminded herself that she

would be approaching the Gotham Book Mart, home of the James Joyce Society, at

almost the same hour in which Leopold Bloom, the hero of Ulysses, had walked

out upon Sandymount Beach. “And had I any sense at all,” Kate thought, “I would

be on a beach myself.” But having become temporary custodian of the Samuel

Lingerwell papers, and thus unexpectedly involved in the literary

correspondence of James Joyce, Kate thought it only proper that she attend

tonight’s celebration.

The Gotham Book Mart, on New York’s West Forty-seventh Street, welcomes members of the James Joyce Society into a room at the rear of the shop. Kate was somewhat surprised to discover how many men were present – not only prominent Joyce scholars, but young men, the sort one least expected to encounter at the meetings of a literary society. But the reason was not far to seek. Writing their doctoral dissertations on Joyce, they hoped to come upon some secret, still undiscovered clue in the labyrinth of his works, which would make their academic fortune. For Joyce had by now, in the United States, added to all his other magic powers that of being able to bestow an academic reputation. (Cross 9-10)

There are passing references to Joyce throughout this murder mystery novel, though most of the action centres in the Berkshires County of Massachusetts, where English Literature academics in weekenders meet the world of dairy farmers and the unread. The chapters use the titles of stories in Dubliners, witty allusions being made to these titles in their respective chapters, and most of the action occurs in and around Amanda Cross’s resident town of Alford, disguised under the name Araby. Her job is to work with a selected assistant to arrange the Joyce-Lingerwell correspondence stored in a country house. But, being a murder story, there is a murder which she then has to solve.

The Prologue implies that in 1966 Bloomsday is clubbish, a kind of pastime for gentlemen academics and magnet for young male students fishing for a fresh angle for a thesis about Ulysses. The plot reinforces Flann O’Brien’s celebrated jests about Joyce turning into an American university industry, amplified in Patrick Kavanagh’s poem ‘Who Killed James Joyce?’ Their 1954 Bloomsday was an all-male show and Kate Fansler makes pointed remarks throughout the novel to the effect that Joyce studies in 1964, and academic life in general, is a man’s world. Bloomsday is a secret meeting for those in-the-know, where men talk to men and women might show up. The nascent feminism animating the whole novel is expressed directly at every turn, as for example when we are told, “Kate [Fansler] was not a member of the James Joyce Society, but the name of Samuel Lingerwell assured her entrance, a welcome, a glass of the Swiss wine Joyce had especially favored.” (Cross 10) The reader is led to understand that Joyce is a mine of ideas waiting to be exploited, an object of postgraduate game-playing, brilliant but brittle. It is the monolith of Modernism that can be scaled from any direction. It does not appear that members engage in Joycean festivities beyond the walls of the Society rooms, or university tutorials. It is an event for literary insiders. The ironies of the name of the mythical correspondent Lingerwell resonate throughout.

Incidentally,

the James Joyce Society itself was founded in 1947 and still operates in New York,

though not at the Gotham Book Mart, which closed in 2007. It’s first member was

T. S. Eliot, no less. So this was an established location of Bloomsday and one

mode of Joycean enjoyment.

Comments

Post a Comment